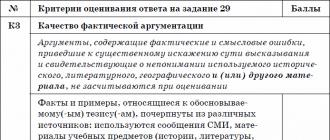

Great altar to Zeus. Pergamon altar. Perception in the 20th century

The Pergamon altar was built in honor of the battle of the Pergamon king over the barbarians (Gauls),

the allegory of the altar is simple - the gods personify the Greeks, the giants - the Gauls. The gods embody the idea of a well-ordered state life, the giants - the unexpired tribal traditions of the aliens, their exceptional militancy and aggressiveness.The theme of the frieze is gigantomachy. The son of Gaia - the mother of the earth, (and she, as I understand it,is the grandmother of the Olympian gods. Doesn't it sound unusual, Gaia is the grandmother of the Olympic gods?)rose to fight for a place on Olympus.In total, the frieze depicts about fifty figures of gods and the same number of giants. The gods are located in the upper part of the frieze, and their opponents are in the lower one, which emphasizes the opposition of the two worlds, the “upper” (divine) and the “lower” ( chthonic). The gods are anthropomorphic, the giants retain the features of animals and birds: some of them have snakes instead of legs, wings behind their backs. The names of each of the gods and giants, explaining the images, are neatly carved below the figures on the cornice.

Altar model

Along the perimeter of the basement, the famous big frieze(2.3 m high and 120 m long), covering the high smooth wall of the plinth and the side walls of the stairs.

Distribution of gods:

- East side (main) - Olympian gods

- north side gods of the night and constellations

- West side - deities of the water element

- South sidegods of heaven and heavenly bodies.

High high relief allows you to distinguish all the details of the composition. The figures of gods and giants are presented in the entire height of the frieze, one and a half times higher than human height. Gods and giants are depicted in full growth, many giants have snakes instead of legs. The relief shows huge snakes and predatory animals taking part in the battle.

The background between the figures is filled with fluttering fabrics, wings and snake tails. Initially, all the figures were painted, many details were gilded. (Can you imagine that?) A special compositional technique was used - extremely dense filling of the surface with images that leave almost no free background. This is a remarkable feature of the composition of this monument. Throughout the frieze, not a single piece of sculptural space remains that is not involved in the active action of a fierce struggle. With a similar technique, the creators of the altar give the picture of martial arts a universal character. The structure of the composition, in comparison with the classical standard, has changed: the opponents fight so closely that their mass suppresses space, and the figures are intertwined.

The fighting figures retreat from the walls, push through the space of their divine world and find themselves in our world of people. People climbing the stairs become participants in the battle, the outcome of which is the victory of the gods, each new step up the stairs is a step towards victory.

The main feature of this sculpture is extreme energy and expressiveness.

In the Pergamon frieze, one of the essential aspects of Hellenistic art was most fully reflected - the special grandeur of the images, their superhuman strength, exaggeration of emotions, and stormy dynamics.

The reliefs of the Pergamon altar are one of the best examples of Hellenistic art, which for the sake of these qualities abandoned the tranquility of the classics. “Although battles and skirmishes were a frequent theme in ancient reliefs, they have never been depicted in the same way as on the Pergamon altar, with such a shuddering sense of cataclysm, battles not for life, but for death, where all cosmic forces, all demons of the earth participate. and the sky."

“The scene is full of great tension and has no equal in ancient art. The fact that in the IV century. BC e. was only outlined by Scopas as a breakdown of the classical ideal system, here it reaches its highest point. The faces distorted by pain, the mournful looks of the vanquished, the piercing torment - everything is now shown with obviousness. early classical art before Phidias also loved dramatic themes, but there the conflicts were not brought to a cruel end. Gods like Athena Myron only warned the guilty of the consequences of their disobedience. In the era of Hellenism, they physically deal with the enemy. All their huge bodily energy, superbly conveyed by the sculptors, is aimed at the act of punishment.

The masters emphasize the furious pace of events and the energy with which the opponents are fighting: the swift onslaught of the gods and the desperate resistance of the giants. Due to the abundance of details and the density of filling the background with them, the effect of noise that accompanies the battle is created - you can feel the rustle of wings, the rustle of snake bodies, the ringing of weapons.

The energy of the images is promoted by the type of relief chosen by the masters - high. Sculptors actively work with a chisel and drill, cutting deeply into the thickness of the marble and creating large differences in planes. Thus, there is a noticeable contrast of illuminated and shaded areas. These light and shadow effects add to the feeling of intense combat.

The peculiarity of the Pergamon altar is a visual transmission of the psychology and mood of those depicted. The delight of the winners and the tragedy of the doomed giants are clearly read. The scenes of death are full of deaf sorrow and genuine despair. All shades of suffering unfold before the viewer. In the plasticity of faces, postures, movements and gestures, a combination of physical pain and deep moral suffering of the vanquished is conveyed.

The Olympian gods no longer bear the stamp of Olympian calm on their faces: the muscles are tense and the eyebrows are furrowed. At the same time, the authors of the reliefs do not abandon the concept of beauty - all participants in the battle are beautiful in face and proportions, there are no scenes that cause horror and disgust. Nevertheless, the harmony of the spirit is already wavering - faces are distorted by suffering, deep shadows of the orbits of the eyes, serpentine strands of hair are visible.

The sketch of the frieze was created by one artist. Upon close examination of the frieze, coordinated to the smallest detail, it becomes obvious that nothing was left to chance. Each fighting group has its own composition, even the hairstyles and shoes of the goddesses do not occur twice.

In the course of the studies, differences were established, indicating that several masters worked on the relief, which, however, had practically no effect on the consistency of the whole work and its general perception. Masters from different parts of Greece embodied a single project created by the chief master, which is confirmed by the surviving signatures of masters from Athens and Rhodes. The sculptors were allowed to leave their names on the lower plinth of the frieze fragment they made, but these signatures are practically not preserved, which does not allow us to draw a conclusion about the number of craftsmen who worked on the frieze. By examining the inscription of symbols in the signatures, scientists were able to establish that two generations of sculptors took part in the work - the older and the younger, which makes the consistency of this sculptural work even more appreciated.

And also about how useful it is to build roads ....

Greek temples at Paestum were discovered by portly builders, as was the Pergamon altar.

In the 19th century the Turkish government invited German specialists to build roads: with 1867

on 1873

gg. work in Asia Minor engineer Carl Humann. Previously, he visited ancient Pergamon in winter 1864

—1865

gg. He discovered that no full-fledged excavations had yet been carried out in Pergamon and the finds could be of extraordinary value.

V 1878

On September 9, the first excavations began at Pergamum, lasting one year. Large fragments were unexpectedly discovered frieze altar of extraordinary artistic value and numerous sculptures.

Germany quickly appreciated the sensationalism and significance of the finds, Hoemann became a celebrity. Fragments of the altar were taken to Germany for restoration, the altar is exhibited in the "Pergamum Museum" created specifically for this purpose.

"When we were rising, seven huge eagles soared over acropolis foreshadowing happiness. They dug up and cleared the first slab. It was a mighty giant on serpentine writhing legs, facing us with a muscular back, his head turned to the left, with a lion's skin on his left hand ... They turn over another plate: the giant falls back onto a rock, lightning pierced his thigh - I feel your closeness, Zeus!

I frantically run around all four plates. I see the third approaching the first: the serpentine ring of the big giant clearly passes to the slab with the giant kneeling down… I positively tremble all over. Here's another piece - I'm scraping the ground with my nails - it's Zeus! The great and wonderful monument is once again presented to the world, all our works are crowned, group Athens received the most beautiful pandan…

Deeply shaken, we, three happy people, stood around the precious find, until I sank down on the stove and relieved my soul with large tears of joy. Carl Humann

In 1945, the Pergamon Altar was taken to the USSR as a trophy, returned to Berlin in 1958, but casts were made, which were transferred to the fund of the St. A copy of the altarpiece is located in the gallery of the main hall of the Baron Stieglitz Museum, under a glass dome.

Three moira their bronze maces inflict mortal blows on Agria and Foant

Nereus, Dorida and Ocean

"Battle of ZeusWith Porphyrion»:

Zeus is fighting simultaneously with three opponents. Having struck one of them, he prepares to throw his lightning at the leader of the enemies - the snake-headed giant Porfirion.

"Battle Athens With Alcyoneem»:

the goddess with a shield in her hands threw the winged giant Alcyoneus to the ground. The winged goddess of victory rushes to her Nika to crown your head laurel wreath. The giant unsuccessfully tries to free himself from the hand of the goddess.

Goddess Mother of Giants Gaia, rising from the earth, vainly begs Athena to spare her son - the giant Alcyoneus

The altar of Zeus in Pergamon is one of the most remarkable creations of the Hellenistic period.

The Pergamon state reached its peak by the middle of the 3rd century BC, when the kings of the Attalid dynasty ruled there. On income from trade and taxes, the Attalids launched a gigantic construction activity. The central part of the capital of the state, its acropolis, towering 270 meters above the surrounding territory, was built up with numerous buildings. All these structures were arranged in a fan-like manner and constituted one architectural ensemble. Among them, the royal palaces, famous for their magnificent mosaic floors, a theater with ninety rows, a gymnasium, a temple of Athena, a library with halls decorated with sculptural portraits of famous historians and poets, stood out in particular. The Pergamon Library was the richest collection of manuscripts - up to two hundred thousand scrolls. The Pergamon Library rivaled that of Alexandria.

The Pergamon school, more than other schools of that time, gravitated toward pathos and drama, continuing the traditions of Scopas. Its artists did not always resort to mythological subjects, as was customary in the classical era. On the square of the Pergamon Acropolis, there were sculptural groups commemorating the victory over the "barbarians" - the tribes of the Gauls who besieged the Kingdom of Pergamon. In works full of expression and dynamics, the artists pay tribute to the vanquished, showing them both valiant and suffering.

In their art, the Greeks did not stoop to humiliate their opponents. This feature of ethical humanism comes out with particular clarity when the "barbarians" are depicted realistically. Moreover, after the campaigns of Alexander the Great, in general, much has changed in relation to foreigners. As Plutarch writes, Alexander considered himself the reconciler of the universe, "making everyone drink ... from the same cup of friendship and mixing together lives, morals, marriages and forms of life."

Morals and forms of life, as well as forms of religion, indeed began to mix in the Hellenistic era, but peace did not reign. Discord and war continued. The wars of Pergamum with the Gauls are just one of the episodes. When, finally, the victory over the "barbarians" was finally obtained, in honor of her, the altar of Zeus was erected, completed in 180 BC.

Of the ancient authors, the Roman writer of the 2nd-3rd centuries, Lucius Ampelius, briefly mentions the altar of Zeus in his essay “On the Wonders of the World”. In 1878, German archaeologists excavating at the site of ancient Pergamon managed to find the foundations of the altar and many slabs with reliefs that once adorned the Pergamon altar. After the excavations were completed, all the slabs found were transported to Berlin, restored, and in 1930 included in the reconstruction of the altar.

The altar was a structure with the following dimensions: length - 36 meters, width - 34, height - 9 meters. Twenty steps of the majestic staircase led to the platform of the second tier, surrounded on three sides by a double Ionian colonnade. The platform of the second tier was limited on three sides by blank walls. These walls were decorated with a meter-long small frieze.

On it you can get acquainted with scenes from the life of the local hero Telef, the son of Hercules. The figures of this frieze were depicted against the backdrop of a landscape. Events unfold before the viewer in a continuous sequence of episodes, carefully linked to their surroundings. Thus, this is one of the first examples of the "continuous narrative" that would later become widespread in ancient Roman sculpture. Modeling of figures is moderate, but rich in nuances and shades.

In the center of the colonnade was the altar of Zeus, 3-4 meters high. The roof of the building was crowned with statues. The building of the altar, its statues and sculptural friezes were made of local Pergamon marble.

The decoration of the altar of Zeus and its main attraction is the so-called large frieze / adorned the marble walls of the altar. The length of this wonderful sculptural frieze reached 120 meters.

Here, the long-term war with the "barbarians" appeared as a gigantomachy - the struggle of the Olympic gods with the giants. According to ancient myth, giants - giants who lived far to the west, the sons of Gaia (Earth) and Uranus (Heaven) - rebelled against the Olympians. However, they were defeated by them after a fierce battle and buried under volcanoes, in the deep bowels of mother earth. They remind of themselves with volcanic eruptions and earthquakes.

Particularly impressive is the group in which the fighting goddess of the hunt Artemis is represented. Artemis, a slender girl with a bow in her hands and a quiver over her shoulders, tramples on the chest of a giant with her right foot, which she has cast to the ground. The goddess of the hunt is preparing to enter into a decisive battle with the young giant standing to her left.

The central figure of the composition is Zeus, who surpasses all in size and power. Zeus fights three giants at once. Mighty bodies pile up, intertwine, like a ball of snakes, defeated giants are tormented by shaggy-maned lions, dogs dig in their teeth, horses trample underfoot, but the giants fight fiercely, their leader Porfirion does not retreat before Zeus the Thunderer.

Next to Zeus is his beloved daughter Athena. With her right hand, she grabbed the hair of the young giant and tears him from mother earth. In vain, the goddess of the earth, Gaia, asks to spare the youngest of her sons. Death torment distorted the face of Athena's opponent.

Although battles and skirmishes were a frequent theme in ancient reliefs, they have never been portrayed in the way they were on the Pergamon altar, with such a shuddering sense of cataclysm, life-and-death battles, where all cosmic forces, all demons of the earth and sky. The structure of the composition has changed, which has lost its classical clarity.

In the Pergamon Frieze, the opponents fight so closely that the mass has overwhelmed space, and all the figures are so intertwined that they form a turbulent mess of bodies, though still classically beautiful. Beautiful Olympians, beautiful and their enemies. But the harmony of the spirit fluctuates. Faces are distorted by suffering, deep shadows are visible in the orbits of the eyes, serpentine tossing hair ... The Olympians still triumph over the forces of the underground elements, but this victory is not for long - the elemental principles threaten to blow up a harmonious, harmonious world.

The Russian writer I. S. Turgenev, having examined the fragments of the relief that had just been brought to the Berlin Museum in 1880, expressed his impressions of the Pergamon Altar in this way: falls headlong, with his back to the viewer, into the abyss; on the other hand, another giant rises, with fury on his face, obviously the main fighter, and, straining his last strength, shows such contours of muscles and torso that Michelangelo would have been delighted with. Above Zeus, the goddess of victory soars, expanding her eagle wings, and lifts high the palm of triumph; the god of the sun, Apollo, in a long light chiton, through which his divine, youthful members clearly protrude, rushes on his chariot, carried by two horses as immortal as himself; Eos (Aurora) precedes him, sitting sideways on another horse, in flowing clothes intercepted on his chest, and, turning to his god, calls him forward with a wave of his bare hand; the horse under it also - and as if consciously - turns its head back; under the wheels of Apollo, a crushed giant dies - and words cannot convey that touching and tender expression with which the oncoming death illuminates his heavy features; already one of his hanging, weakened, also dying hand is a miracle of art, which would be worth admiring in order to purposely go to Berlin ...

... All these are now radiant, now formidable, living, dead, triumphant, perishing figures, these coils of scaly snake rings, these outstretched wings, these eagles, these horses, weapons, shields, these flying clothes, these palm trees and these bodies, the most beautiful human bodies in all positions, bold to the point of improbability, slender to the point of music—all these varied facial expressions, selfless movements of limbs, this triumph of malice, and despair, and divine gaiety, and divine cruelty—all this heaven and all this earth—yes, this is the world, the whole world, before the revelation of which an involuntary coldness of delight and passionate reverence runs through all the veins.

By the end of the 2nd century BC, the Kingdom of Pergamon, like other Hellenistic states, entered a period of internal crisis and political subordination to Rome. Carthage fell in 146 BC. That was a turning point. Rome later took over Greece, destroying Corinth to its foundations. In 30 BC, Egypt also became part of the Roman Empire. Since that time, the culture of the Pergamon state no longer bears such rich fruits, since it descends to the position of one of the Roman provinces.

I can well imagine the shock of Karl Humann (the engineer who opened the altar). And now I also know thatInitially, all the figures were painted, many details were gilded.

Variant plot of the Pergamon altar proposed

Which in the subordinate clause mentions the Pergamon altar, comparing the traditions of sacrifice in Olympia, this is the only mention of the altar in all the surviving written sources of antiquity. This is all the more surprising because, most likely, the altar was still considered a masterpiece, since Lucius Ampelius ranks it among the wonders of the world. This silence of the sources is interpreted in different ways. A possible explanation is that the Hellenistic monument could be perceived by the Romans as insignificant, since it did not originate in the classical era and did not come out of real Greek, primarily Attic workshops. The only depiction of an altar in antiquity is found on a Roman coin of the imperial time, which represents the altar in a stylized form.

In the New Testament

When an earthquake struck the city in the Middle Ages, the altar, like many other structures, was buried underground.

Altar discovery

| “When we climbed, seven huge eagles soared over the acropolis, foreshadowing happiness. They dug up and cleared the first slab. It was a mighty giant on serpentine writhing legs, facing us with a muscular back, his head turned to the left, with a lion's skin on his left hand ... They turn over another plate: the giant falls back onto a rock, lightning pierced his thigh - I feel your closeness, Zeus! I frantically run around all four plates. I see the third approaching the first: the serpentine ring of the big giant clearly passes to the slab with the giant kneeling down… I positively tremble all over. Here's another piece - I scrape the ground with my nails - this is Zeus! The great and wonderful monument was once again presented to the world, all our works were crowned, Athena's group received the most beautiful pandanus... |

| Carl Human |

In the 19th century the Turkish government invited German specialists to build roads: from to . work in Asia Minor was carried out by engineer Karl Human. Previously, he visited ancient Pergamon in the winter - gg. He discovered that Pergamon had not yet been fully excavated, although the finds may be of extraordinary value. Human had to use all his influence in order to prevent the destruction of part of the open marble ruins in the limestone - gas ovens. But real archaeological excavations required support from Berlin.

Altar in Russia

After World War II, the altar, among other valuables, was removed from Berlin by Soviet troops. Since 1945, it has been kept in the Hermitage, where in 1954 a special room was opened for it, and the altar became available to visitors

General characteristics of the structure

The innovation of the creators of the Pergamon Altar was that the altar was turned into an independent architectural structure.

It was erected on a special terrace on the southern slope of the mountain of the acropolis of Pergamon, below the sanctuary of Athena. The altar was almost 25 m lower than the other buildings and was visible from all sides. It offered a beautiful view of the lower city with the temple of the god of healing Asclepius, the sanctuary of the goddess Demeter and other structures.

The altar was intended for worship in the open air. It was a high plinth (36.44 × 34.20 m) raised on a five-level foundation. On one side, the plinth was cut through by a wide open marble staircase 20 m wide, leading to the upper platform of the altar. The upper tier was surrounded by an Ionic portico. Inside the colonnade there was an altar courtyard, where the actual altar was located (3-4 m high). The platform of the second tier was limited on three sides by blank walls. The roof of the building was crowned with statues. The whole structure reached a height of about 9 m. Along the perimeter of the plinth, the famous big frieze(2.3 m high and 120 m long), covering the high smooth wall of the plinth and the side walls of the stairs. The upper edge of the frieze was completed by a crenellated cornice. On the inner walls of the altar courtyard was the second frieze of the Pergamon altar, Small, dedicated to the history of Telef (1 m high).

Reconstruction and current state

Gigantomachy was a common subject of ancient plastic arts. But this plot was comprehended at the Pergamon court in accordance with political events. The altarpiece reflected the ruling dynasty's perception and the state's official ideology of victory over the Galatians. In addition, the Pergamians perceived this victory deeply symbolically, as the victory of the greatest Greek culture over barbarism.

“The semantic basis of the relief is a clear allegory: the gods personify the world of the Greeks, the giants - the Gauls. The gods embody the idea of a well-ordered state life, the giants - the unexpired tribal traditions of the newcomers, their exceptional militancy and aggressiveness. The allegory of another kind forms the basis of the content of the famous frieze: Zeus, Hercules, Dionysus, Athena are the personification of the dynasty of the Pergamon kings.

In total, the frieze depicts about fifty figures of gods and the same number of giants. The gods are located in the upper part of the frieze, and their opponents are in the lower one, which emphasizes the opposition of the two worlds, the "upper" (divine) and the "lower" (chthonic). The gods are anthropomorphic, the giants retain the features of animals and birds: some of them have snakes instead of legs, wings behind their backs. The names of each of the gods and giants, explaining the images, are neatly carved below the figures on the cornice.

Distribution of gods:

- East side (main)- Olympic gods

- north side- gods of the night and constellations

- West side- deities of the water element

- South side- gods of heaven and heavenly bodies

"The Olympians triumph over the forces of the underground elements, but this victory is not for long - the elemental principles threaten to blow up a harmonious, harmonious world."

| Illustration | Description | Detail |

|---|---|---|

| "Battle of Zeus with Porphyrion": Zeus is fighting simultaneously with three opponents. Having struck one of them, he prepares to throw his lightning at the leader of the enemies - the snake-headed giant Porfirion. | ||

| "Battle of Athena with Alcyoneus": the goddess with a shield in her hands threw the winged giant Alcyoneus to the ground. The winged goddess of victory Nike rushes towards her to crown her head with a laurel wreath. The giant unsuccessfully tries to free himself from the hand of the goddess. | ||

| "Artemis" | ||

Masters

The sculptural decoration of the altar was made by a group of craftsmen according to a single project. Some names are mentioned - Dionysiades, Orestes, Menekrates, Pyromachus, Isigon, Stratonicus, Antigonus, but it is not possible to attribute any fragment to a specific author. Although some of the sculptors belonged to the classical Athenian school of Phidias, and some were of the local Pergamene style, the whole composition gives a coherent impression.

Until now, there is no unequivocal answer to the question of how the masters worked on the giant frieze. There is no consensus on the extent to which the individual personalities of the masters influenced the appearance of the frieze. There is no doubt that the sketch of the frieze was created by a single artist. Upon close examination of the frieze, coordinated to the smallest detail, it becomes obvious that nothing was left to chance. . Already broken down into struggling groups, it is striking that none of them is similar to the other. Even the hairstyles and shoes of the goddesses do not occur twice. Each of the fighting groups has its own composition. Therefore, the created images themselves rather than the styles of the masters have an individual character.

In the course of the research, differences were established, indicating that several masters worked on the relief, which, however, practically did not affect the consistency of the whole work and its general perception. Masters from different parts of Greece embodied a single project created by the chief master, which is confirmed by the surviving signatures of masters from Athens and Rhodes. The sculptors were allowed to leave their names on the lower plinth of the frieze fragment they made, but these signatures are practically not preserved, which does not allow us to draw a conclusion about the number of craftsmen who worked on the frieze. Only one signature on the southern risalit has been preserved in a condition suitable for identification. Since there was no plinth on this section of the frieze, the name "Theorretos" was carved next to the created deity. By examining the inscription of symbols in the signatures, scientists were able to establish that two generations of sculptors took part in the work - the older and the younger, which makes the consistency of this sculptural work even more appreciated. .

Description of sculptures

| “... Under the wheels of Apollo, a crushed giant dies - and words cannot convey that touching and touching expression with which the oncoming death enlightens his heavy features; already one of his hanging, weakened, also dying hand is a miracle of art, which would be worth admiring in order to purposely go to Berlin ... ... All of these - now radiant, now formidable, living, dead, triumphant, perishing figures, these coils of scaly snake rings, these outstretched wings, these eagles, these horses, weapons, shields, these flying clothes, these palm trees and these bodies, the most beautiful human bodies in all positions, bold to the point of improbability, slender to the point of music - all these diverse facial expressions, selfless movements of members, this triumph of malice, and despair, and divine gaiety, and divine cruelty - all this heaven and all this earth - yes it is the world, the whole world, before the revelation of which an involuntary coldness of delight and passionate reverence runs through all the veins. |

| Ivan Turgenev |

The figures are made in very high relief (high relief), they are separated from the background, practically turning into a round sculpture. This type of relief gives deep shadows (contrasting chiaroscuro), making it easy to distinguish all the details. The compositional structure of the frieze is exceptionally complex, plastic motifs are rich and varied. Unusually convex figures are depicted not only in profile (as was customary in relief), but also in the most complex turns, even from the front and from the back.

The figures of gods and giants are presented in the entire height of the frieze, one and a half times higher than human height. Gods and giants are depicted in full growth, many giants have snakes instead of legs. The relief shows huge snakes and predatory animals taking part in the battle. The composition consists of many figures built into groups of opponents colliding in a duel. The movements of groups and characters are directed in different directions, in a certain rhythm, while maintaining the balance of the components on each side of the building. Images also alternate - beautiful goddesses are replaced by scenes of the death of zoomorphic giants.

The conventions of the depicted scenes are compared with the real space: the steps of the stairs, along which those going to the altar climb, also serve for the participants in the battle, who either “kneel” on them, or “walk” along them. The background between the figures is filled with fluttering fabrics, wings and snake tails. Initially, all figures were painted, many details were gilded. A special compositional technique was used - extremely dense filling of the surface with images that practically do not leave a free background. This is a remarkable feature of the composition of this monument. Throughout the frieze, not a single piece of sculptural space remains that is not involved in the active action of a fierce struggle. With a similar technique, the creators of the altar give the picture of martial arts a universal character. The structure of the composition, in comparison with the classical standard, has changed: the opponents fight so closely that their mass suppresses space, and the figures are intertwined.

Style characteristic

The main feature of this sculpture is extreme vigor and expressiveness.

The reliefs of the Pergamon altar are one of the best examples of Hellenistic art, which for the sake of these qualities abandoned the tranquility of the classics. “Although battles and skirmishes were a frequent theme in ancient reliefs, they have never been depicted in the same way as on the Pergamon altar - with such a shuddering sense of cataclysm, battles not for life, but for death, where all cosmic forces, all demons of the earth participate and the sky."

“The scene is full of great tension and has no equal in ancient art. The fact that in the IV century. BC e. was only outlined by Scopas as a breakdown of the classical ideal system, here it reaches its highest point. The faces distorted by pain, the mournful looks of the vanquished, the piercing flour - everything is now shown with obviousness. Early classical art before Phidias also loved dramatic themes, but there conflicts were not brought to a violent end. The gods, like Myron's Athena, only warned the guilty about the consequences of their disobedience. In the era of Hellenism, they physically deal with the enemy. All their huge bodily energy, superbly conveyed by the sculptors, is directed to the act of punishment.

The masters emphasize the furious pace of events and the energy with which the opponents are fighting: the swift onslaught of the gods and the desperate resistance of the giants. Due to the abundance of details and the density of filling the background with them, the effect of noise that accompanies the battle is created - the rustle of wings, the rustle of snake bodies, the ringing of weapons are felt.

The energy of the images is promoted by the type of relief chosen by the masters - high. Sculptors actively work with a chisel and drill, cutting deeply into the thickness of the marble and creating large differences in planes. Thus, there is a noticeable contrast of illuminated and shaded areas. These light and shadow effects add to the feeling of intense combat.

The peculiarity of the Pergamon altar is a visual transmission of the psychology and mood of those depicted. The delight of the winners and the tragedy of the doomed giants are clearly read. The scenes of death are full of deaf sorrow and genuine despair. All shades of suffering unfold before the viewer. In the plasticity of faces, postures, movements and gestures, a combination of physical pain and deep moral suffering of the vanquished is conveyed.

The Olympian gods no longer bear the stamp of Olympian calm on their faces: the muscles are tense and the eyebrows are furrowed. At the same time, the authors of the reliefs do not abandon the concept of beauty - all participants in the battle are beautiful in face and proportions, there are no scenes that cause horror and disgust. Nevertheless, the harmony of the spirit is already wavering - faces are distorted by suffering, deep shadows of the eye orbits, serpentine strands of hair are visible.

Inner small frieze (history of Telef)

The frieze was dedicated to the life and deeds of Telef, the legendary founder of Pergamon. The rulers of Pergamon revered him as their ancestor.

The inner small frieze of the Pergamon Altar of Zeus (170-160 BC), which does not have the plastic force of a generalized cosmic character, is associated with more specific mythological scenes and tells about the life and fate of Telef, the son of Hercules. It is smaller in size, its figures are calmer, more concentrated, sometimes, which is also characteristic of Hellenism, elegiac; there are elements of the landscape. The surviving fragments depict Hercules wearily leaning on a club, the Greeks are busy building a ship for the travel of the Argonauts. In the plot of the small frieze, the theme of surprise, a favorite in Hellenism, was the effect of Hercules recognizing his son Teleph. So the pathetic regularity of the death of giants and the chance prevailing in the world determined the themes of the two Hellenistic friezes of the altar of Zeus.

Events unfold before the viewer in a continuous sequence of episodes, carefully linked to their surroundings. Thus, this is one of the first examples of the "continuous narrative" that would later become widespread in ancient Roman sculpture. Modeling of figures is moderate, but rich in nuances and shades.

Relationship with other works of art

In many episodes of the altar frieze one can recognize other ancient Greek masterpieces. So, the idealized pose and beauty of Apollo resemble the classic statue known in ancient times by the sculptor Leochar, created 150 years before the Pergamon frieze and preserved to this day in a Roman copy of Apollo Belvedere. The main sculptural group - Zeus and Athena - reminds of how the fighting figures disperse, the image of the duel between Athena and Poseidon on the western pediment of the Parthenon. (These references are not accidental, as Pergamon saw itself as the new Athens.) . The frieze itself influenced later antique work. Most famous example is the Laocoon sculptural group, which, as proved by Bernard Andre, was created twenty years later than the Pergamon high relief. The authors of the sculptural group worked directly in the tradition of the creators of the altar frieze and possibly even participated in the work on it.

Perception in the 20th century

Probably the most obvious example of the reception of the altar was the museum building built for the Pergamon altar. The building, designed by Alfred Messel in the -1930s, is a giant copy of the façade of the chancel.

The use of the Pergamon Altar in the campaign to nominate Berlin as the venue for the 2000 Summer Olympics caused dissatisfaction with the press and the public. The Senate of Berlin invited members of the International Olympic Committee to a gala dinner in the artistic setting of the Pergamon Altar. Such a dinner at the Pergamon Altar had already taken place on the eve of the 1936 Olympic Games, to which the members of the Olympic Committee were invited by the Minister of the Interior of National Socialist Germany, Wilhelm Frick.

They also mention that when creating the Lenin Mausoleum, A.V. Shchusev was guided by the forms of not only the pyramid of Djoser and the tomb of Cyrus, but also the Pergamon altar.

Author's graphic recreation of Andrey Alexander

Russian photographer, director and actor Andrey Alexander presented his version of the restoration of the large frieze of the Pergamon Altar in 2013. In two years, he managed to recreate the lost parts by borrowing other sculptures, as well as photographs of living people. The first presentation of the work took place at the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts from April 22 to July 29, 2013.

Write a review on the article "Pergamon Altar"

Notes

- Pausanias, 5,13,8.

- Steven J. Friesen. Satan's Throne, Imperial Cults and the Social Settings of Revelation // Journal for the Study of the New Testament, 3/27/2005, pp. 351-373

- Ch. 2. Revelation // / Ed. A. P. Lopukhina

- Around the world #8 (2599) | August 1990

- Michael Vickers "The Thunderbolt of Zeus: Yet More Fragments of the Pergamon Altar in the Arundel Collection" American Journal of Archeology 89.3 (July 1985), pp 516-519.

- , Zabern, Mainz 1992, p. 36

- Die Antikensammlung im Pergamonmuseum und in Charlottenburg, von Zabern, Mainz 1992, S. 35f.

- Bernard Andrew: Laokoon or die Gründung Roms

- Schalles: Pergamonaltar, columns 212-214.

- Schalles: Pergamonaltar, columns 211-212.

- Schalles: Pergamonaltar, columns 214-215.

- ;

Links

Literature

- Heinrich Stol. Gods and Giants

- Tseren E. Biblical Hills. Moscow: Nauka, 1966.

- Ivan Turgenev. Pergamon excavations. 1880

- Klimov O. Yu. Kingdom of Pergamon. Problems of political history and state structure. St. Petersburg: Faculty of Philology and Arts; Nestor-History, 2010. S. 327-343. ISBN 978-5-8465-0702-9

An excerpt characterizing the Pergamon altar

In the booth, which Pierre entered and in which he stayed for four weeks, there were twenty-three captured soldiers, three officers and two officials.All of them then appeared to Pierre as if in a fog, but Platon Karataev remained forever in Pierre's soul the strongest and dearest memory and personification of everything Russian, kind and round. When the next day, at dawn, Pierre saw his neighbor, the first impression of something round was completely confirmed: the whole figure of Plato in his French overcoat belted with a rope, in a cap and bast shoes, was round, his head was completely round, back, chest, shoulders, even the arms that he wore, as if always about to embrace something, were round; a pleasant smile and large brown gentle eyes were round.

Platon Karataev must have been over fifty years old, judging by his stories about the campaigns in which he participated as a longtime soldier. He himself did not know and could not in any way determine how old he was; but his teeth, bright white and strong, which kept rolling out in their two semicircles when he laughed (as he often did), were all good and whole; not a single gray hair was in his beard and hair, and his whole body had the appearance of flexibility and especially hardness and endurance.

His face, despite the small round wrinkles, had an expression of innocence and youth; his voice was pleasant and melodious. But the main feature of his speech was immediacy and argumentativeness. He apparently never thought about what he said and what he would say; and from this there was a special irresistible persuasiveness in the speed and fidelity of his intonations.

His physical strength and agility were such during the first time of captivity that he did not seem to understand what fatigue and illness were. Every day in the morning and in the evening, lying down, he said: “Lord, put it down with a pebble, raise it up with a ball”; in the morning, getting up, always shrugging his shoulders in the same way, he would say: "Lie down - curled up, get up - shake yourself." And indeed, as soon as he lay down to immediately fall asleep like a stone, and as soon as he shook himself, in order to immediately, without a second of delay, take up some business, the children, having risen, take up toys. He knew how to do everything, not very well, but not badly either. He baked, steamed, sewed, planed, made boots. He was always busy and only at night allowed himself to talk, which he loved, and songs. He sang songs, not like songwriters sing, knowing that they are being listened to, but he sang like birds sing, obviously because it was just as necessary for him to make these sounds, as it is necessary to stretch or disperse; and these sounds were always subtle, tender, almost feminine, mournful, and his face was very serious at the same time.

Having been captured and overgrown with a beard, he, apparently, threw away everything that was put on him, alien, soldierly, and involuntarily returned to the former, peasant, people's warehouse.

“A soldier on leave is a shirt made of trousers,” he used to say. He reluctantly spoke about his time as a soldier, although he did not complain, and often repeated that he had never been beaten during his entire service. When he told, he mainly told from his old and, apparently, dear memories of the "Christian", as he pronounced, peasant life. The proverbs that filled his speech were not those, for the most part, indecent and glib sayings that the soldiers say, but these were those folk sayings that seem so insignificant, taken separately, and which suddenly acquire the meaning of deep wisdom when they are said by the way.

Often he said the exact opposite of what he had said before, but both were true. He loved to talk and spoke well, embellishing his speech with endearing and proverbs, which, it seemed to Pierre, he himself invented; but the main charm of his stories was that in his speech the simplest events, sometimes the very ones that, without noticing them, Pierre saw, took on the character of solemn decorum. He liked to listen to fairy tales that one soldier told in the evenings (all the same), but most of all he liked to listen to stories about real life. He smiled joyfully as he listened to such stories, inserting words and asking questions that tended to make clear to himself the beauty of what was being told to him. Attachments, friendship, love, as Pierre understood them, Karataev did not have any; but he loved and lived lovingly with everything that life brought him, and especially with a person - not with some famous person, but with those people who were before his eyes. He loved his mutt, loved his comrades, the French, loved Pierre, who was his neighbor; but Pierre felt that Karataev, in spite of all his affectionate tenderness for him (with which he involuntarily paid tribute to Pierre's spiritual life), would not have been upset for a minute by parting from him. And Pierre began to experience the same feeling for Karataev.

Platon Karataev was for all the other prisoners the most ordinary soldier; his name was falcon or Platosha, they good-naturedly mocked him, sent him for parcels. But for Pierre, as he presented himself on the first night, an incomprehensible, round and eternal personification of the spirit of simplicity and truth, he remained so forever.

Platon Karataev knew nothing by heart, except for his prayer. When he spoke his speeches, he, starting them, seemed not to know how he would end them.

When Pierre, sometimes struck by the meaning of his speech, asked to repeat what was said, Plato could not remember what he had said a minute ago, just as he could not in any way tell Pierre his favorite song with words. There it was: “dear, birch and I feel sick,” but the words did not make any sense. He did not understand and could not understand the meaning of words taken separately from the speech. Every word of his and every action was a manifestation of an activity unknown to him, which was his life. But his life, as he himself looked at it, had no meaning as a separate life. It only made sense as a part of the whole, which he constantly felt. His words and actions poured out of him as evenly, as necessary and immediately, as a scent separates from a flower. He could not understand either the price or the meaning of a single action or word.

Having received news from Nikolai that her brother was with the Rostovs in Yaroslavl, Princess Marya, despite her aunt's dissuades, immediately prepared to go, and not only alone, but with her nephew. Whether it was difficult, easy, possible or impossible, she did not ask and did not want to know: her duty was not only to be near, perhaps, her dying brother, but also to do everything possible to bring him a son, and she got up. drive. If Prince Andrei himself did not notify her, then Princess Mary explained this either by the fact that he was too weak to write, or by the fact that he considered this long journey too difficult and dangerous for her and his son.

In a few days, Princess Mary got ready for the journey. Her crews consisted of a huge princely carriage, in which she arrived in Voronezh, chaises and wagons. M lle Bourienne, Nikolushka with her tutor, an old nanny, three girls, Tikhon, a young footman and a haiduk, whom her aunt had let go with her, rode with her.

It was impossible to even think of going to Moscow in the usual way, and therefore the roundabout way that Princess Mary had to take: to Lipetsk, Ryazan, Vladimir, Shuya, was very long, due to the lack of post horses everywhere, it is very difficult and near Ryazan, where, as they said, the French showed up, even dangerous.

During this difficult journey, m lle Bourienne, Dessalles and the servants of Princess Mary were surprised by her fortitude and activity. She went to bed later than everyone else, got up earlier than everyone else, and no difficulties could stop her. Thanks to her activity and energy, which aroused her companions, by the end of the second week they were approaching Yaroslavl.

During the last time of her stay in Voronezh, Princess Marya experienced the best happiness in her life. Her love for Rostov no longer tormented her, did not excite her. This love filled her whole soul, became an indivisible part of herself, and she no longer fought against it. Of late, Princess Marya became convinced—although she never said this clearly to herself in words—she was convinced that she was loved and loved. She was convinced of this during her last meeting with Nikolai, when he came to her to announce that her brother was with the Rostovs. Nikolai did not hint in a single word that now (in the event of the recovery of Prince Andrei) the former relations between him and Natasha could be resumed, but Princess Marya saw from his face that he knew and thought this. And, despite the fact that his relationship to her - cautious, tender and loving - not only did not change, but he seemed to be glad that now the relationship between him and Princess Marya allowed him to more freely express his friendship to her love, as she sometimes thought Princess Mary. Princess Marya knew that she loved for the first and last time in her life, and felt that she was loved, and was happy, calm in this respect.

But this happiness of one side of her soul not only did not prevent her from feeling sorrow for her brother with all her strength, but, on the contrary, this peace of mind in one respect gave her a great opportunity to give herself completely to her feelings for her brother. This feeling was so strong in the first minute of leaving Voronezh that those who saw her off were sure, looking at her exhausted, desperate face, that she would certainly fall ill on the way; but it was precisely the difficulties and worries of the journey, which Princess Marya undertook with such activity, saved her for a while from her grief and gave her strength.

As always happens during a trip, Princess Marya thought about only one trip, forgetting what was his goal. But, approaching Yaroslavl, when something that could lie ahead of her again opened up, and not many days later, but this evening, Princess Mary's excitement reached its extreme limits.

When a haiduk sent ahead to find out in Yaroslavl where the Rostovs were and in what position Prince Andrei was, he met a large carriage driving in at the outpost, he was horrified to see the terribly pale face of the princess, which stuck out to him from the window.

- I found out everything, Your Excellency: the Rostov people are standing on the square, in the house of the merchant Bronnikov. Not far, above the Volga itself, - said the haiduk.

Princess Mary looked at his face in a frightened questioning way, not understanding what he was saying to her, not understanding why he did not answer the main question: what is a brother? M lle Bourienne made this question for Princess Mary.

- What is the prince? she asked.

“Their excellencies are in the same house with them.

“So he is alive,” thought the princess, and quietly asked: what is he?

“People said they were all in the same position.

What did “everything in the same position” mean, the princess did not ask, and only briefly, glancing imperceptibly at the seven-year-old Nikolushka, who was sitting in front of her and rejoicing at the city, lowered her head and did not raise it until the heavy carriage, rattling, shaking and swaying, did not stop somewhere. The folding footboards rattled.

The doors opened. On the left was water - a big river, on the right was a porch; there were people on the porch, servants, and some sort of ruddy-faced girl with a big black plait, who smiled unpleasantly feignedly, as it seemed to Princess Marya (it was Sonya). The princess ran up the stairs, the smiling girl said: “Here, here!” - and the princess found herself in the hall in front of an old woman with an oriental type of face, who, with a touched expression, quickly walked towards her. It was the Countess. She embraced Princess Mary and began to kiss her.

- Mon enfant! she said, je vous aime et vous connais depuis longtemps. [My child! I love you and have known you for a long time.]

Despite all her excitement, Princess Marya realized that it was the countess and that she had to say something. She, not knowing how herself, uttered some courteous French words, in the same tone as those that were spoken to her, and asked: what is he?

“The doctor says there is no danger,” said the countess, but while she was saying this, she raised her eyes with a sigh, and in this gesture there was an expression that contradicted her words.

- Where is he? Can you see him, can you? the princess asked.

- Now, princess, now, my friend. Is this his son? she said, turning to Nikolushka, who was entering with Desalle. We can all fit, the house is big. Oh what a lovely boy!

The countess led the princess into the drawing room. Sonya was talking to m lle Bourienne. The countess caressed the boy. The old count entered the room, greeting the princess. The old count has changed tremendously since the princess last saw him. Then he was a lively, cheerful, self-confident old man, now he seemed a miserable, lost person. He, speaking with the princess, constantly looked around, as if asking everyone whether he was doing what was necessary. After the ruin of Moscow and his estate, knocked out of his usual rut, he apparently lost consciousness of his significance and felt that he no longer had a place in life.

Despite the excitement in which she was, despite one desire to see her brother as soon as possible and annoyance because at that moment, when she only wants to see him, she is occupied and pretended to praise her nephew, the princess noticed everything that was going on around her, and felt the need for a time to submit to this new order into which she was entering. She knew that all this was necessary, and it was difficult for her, but she did not get annoyed with them.

“This is my niece,” said the count, introducing Sonya, “do you not know her, princess?”

The princess turned to her and, trying to extinguish the hostile feeling for this girl that had risen in her soul, kissed her. But it became difficult for her because the mood of everyone around her was so far from what was in her soul.

- Where is he? she asked again, addressing everyone.

“He’s downstairs, Natasha is with him,” answered Sonya, blushing. - Let's go find out. I think you are tired, princess?

The princess had tears of annoyance in her eyes. She turned away and wanted to ask the countess again where to go to him, when light, swift, as if cheerful steps were heard at the door. The princess looked round and saw Natasha almost running in, the same Natasha whom she did not like so much on that old meeting in Moscow.

But before the princess had time to look at the face of this Natasha, she realized that this was her sincere comrade in grief, and therefore her friend. She rushed to meet her and, embracing her, wept on her shoulder.

As soon as Natasha, who was sitting at the head of Prince Andrei, found out about the arrival of Princess Marya, she quietly left his room with those quick, as it seemed to Princess Marya, as if with cheerful steps, and ran to her.

On her excited face, when she ran into the room, there was only one expression - an expression of love, boundless love for him, for her, for everything that was close to a loved one, an expression of pity, suffering for others and a passionate desire to give herself all for in order to help them. It was evident that at that moment not a single thought about herself, about her relationship to him, was in Natasha's soul.

The sensitive Princess Marya, at the first glance at Natasha's face, understood all this and wept on her shoulder with sorrowful pleasure.

“Come on, let’s go to him, Marie,” Natasha said, taking her to another room.

Princess Mary raised her face, wiped her eyes, and turned to Natasha. She felt that she would understand and learn everything from her.

“What…” she began to question, but suddenly stopped. She felt that words could neither ask nor answer. Natasha's face and eyes should have said everything more clearly and deeply.

Natasha looked at her, but seemed to be in fear and doubt - to say or not to say everything that she knew; she seemed to feel that before those radiant eyes, penetrating into the very depths of her heart, it was impossible not to tell the whole, the whole truth as she saw it. Natasha's lip suddenly trembled, ugly wrinkles formed around her mouth, and she, sobbing, covered her face with her hands.

Princess Mary understood everything.

But she still hoped and asked in words in which she did not believe:

But how is his wound? In general, what position is he in?

“You, you ... will see,” Natasha could only say.

They sat for some time downstairs near his room in order to stop crying and come in to him with calm faces.

- How was the illness? Has he gotten worse? When did it happen? asked Princess Mary.

Natasha said that at first there was a danger from a feverish state and from suffering, but in the Trinity this passed, and the doctor was afraid of one thing - Antonov's fire. But that danger was over. When we arrived in Yaroslavl, the wound began to fester (Natasha knew everything about suppuration, etc.), and the doctor said that suppuration could go right. There was a fever. The doctor said that this fever was not so dangerous.

“But two days ago,” Natasha began, “it suddenly happened ...” She restrained her sobs. “I don't know why, but you'll see what he's become.

- Weakened? lost weight? .. - the princess asked.

No, not that, but worse. You will see. Ah, Marie, Marie, he's too good, he can't, can't live... because...

When Natasha, with a habitual movement, opened his door, letting the princess pass in front of her, Princess Marya already felt ready sobs in her throat. No matter how much she prepared herself, or tried to calm down, she knew that she would not be able to see him without tears.

Princess Mary understood what Natasha meant in words: it happened to him two days ago. She understood that this meant that he suddenly softened, and that softening, tenderness, these were signs of death. As she approached the door, she already saw in her imagination that face of Andryusha, which she had known since childhood, tender, meek, tender, which he had so rarely seen and therefore always had such a strong effect on her. She knew that he would say to her quiet, tender words, like those that her father had said to her before his death, and that she could not bear it and burst into tears over him. But, sooner or later, it had to be, and she entered the room. Sobs came closer and closer to her throat, while with her short-sighted eyes she more and more clearly distinguished his form and searched for his features, and now she saw his face and met his gaze.

He was lying on the sofa, padded with pillows, in a squirrel-fur robe. He was thin and pale. One thin, transparently white hand held a handkerchief, with the other, with quiet movements of his fingers, he touched his thin overgrown mustache. His eyes were on those who entered.

Seeing his face and meeting his gaze, Princess Mary suddenly slowed down the speed of her step and felt that her tears had suddenly dried up and her sobs had stopped. Catching the expression on his face and eyes, she suddenly became shy and felt guilty.

“Yes, what am I guilty of?” she asked herself. “In the fact that you live and think about the living, and I! ..” answered his cold, stern look.

There was almost hostility in the deep, not out of himself, but looking into himself look, when he slowly looked around at his sister and Natasha.

He kissed his sister hand in hand, as was their habit.

Hello Marie, how did you get there? he said in a voice as even and alien as his eyes were. If he had squealed with a desperate cry, then this cry would have horrified Princess Marya less than the sound of this voice.

“And did you bring Nikolushka?” he said, also evenly and slowly, and with an obvious effort of recollection.

- How is your health now? - said Princess Marya, herself surprised at what she said.

“That, my friend, you need to ask the doctor,” he said, and, apparently making another effort to be affectionate, he said with one mouth (it was clear that he did not think at all what he was saying): “Merci, chere amie , d "etre venue. [Thank you, dear friend, for coming.]

Princess Mary shook his hand. He winced slightly as he shook her hand. He was silent and she didn't know what to say. She understood what had happened to him in two days. In his words, in his tone, and especially in that cold, almost hostile look, one could feel an estrangement from everything worldly, terrible for a living person. He apparently had difficulty understanding now all living things; but at the same time it was felt that he did not understand the living, not because he was deprived of the power of understanding, but because he understood something else, something that the living did not understand and could not understand and that absorbed him all.

- Yes, that's how strange fate brought us together! he said, breaking the silence and pointing to Natasha. - She keeps following me.

Princess Mary listened and did not understand what he was saying. He, sensitive, gentle Prince Andrei, how could he say this in front of the one he loved and who loved him! If he had thought to live, he would not have said it in such a coldly insulting tone. If he did not know that he was going to die, how could he not feel sorry for her, how could he say this in front of her! There could only be one explanation for this, that it was all the same to him, and all the same because something else, something more important, had been revealed to him.

The conversation was cold, incoherent, and interrupted incessantly.

“Marie passed through Ryazan,” said Natasha. Prince Andrei did not notice that she called his sister Marie. And Natasha, calling her that in his presence, noticed this for the first time.

- Well, what? - he said.

- She was told that Moscow was all burned down, completely, as if ...

Natasha stopped: it was impossible to speak. He obviously made an effort to listen, and yet he couldn't.

“Yes, it burned down, they say,” he said. “It’s very pitiful,” and he began to look ahead, absentmindedly smoothing his mustache with his fingers.

“Have you met Count Nikolai, Marie?” - said Prince Andrei suddenly, apparently wanting to please them. “He wrote here that he was very fond of you,” he continued simply, calmly, apparently unable to understand all the complex meaning that his words had for living people. “If you fell in love with him too, it would be very good ... for you to get married,” he added somewhat more quickly, as if delighted with the words, which he had been looking for a long time and found at last. Princess Marya heard his words, but they had no other meaning for her, except that they proved how terribly far he was now from all living things.

- What can I say about me! she said calmly and looked at Natasha. Natasha, feeling her gaze on her, did not look at her. Again everyone was silent.

“Andre, do you want ...” Princess Mary suddenly said in a trembling voice, “do you want to see Nikolushka?” He always thought of you.

Prince Andrey smiled slightly perceptibly for the first time, but Princess Marya, who knew his face so well, realized with horror that it was not a smile of joy, not tenderness for her son, but a quiet, meek mockery of what Princess Mary used, in her opinion. , the last resort to bring him to his senses.

– Yes, I am very glad to Nikolushka. He is healthy?

When they brought Nikolushka to Prince Andrei, who looked frightened at his father, but did not cry, because no one was crying, Prince Andrei kissed him and, obviously, did not know what to say to him.

When Nikolushka was taken away, Princess Marya went up to her brother again, kissed him, and, unable to restrain herself any longer, began to cry.

He looked at her intently.

Are you talking about Nikolushka? - he said.

Princess Mary, weeping, bowed her head affirmatively.

“Marie, you know Evan…” but he suddenly fell silent.

- What are you saying?

- Nothing. There is no need to cry here,” he said, looking at her with the same cold look.

When Princess Mary began to cry, he realized that she was crying that Nikolushka would be left without a father. With great effort on himself, he tried to go back to life and transferred himself to their point of view.

“Yes, they must feel sorry for it! he thought. “How easy it is!”

“The birds of the air neither sow nor reap, but your father feeds them,” he said to himself and wanted to say the same to the princess. “But no, they will understand it in their own way, they will not understand! They cannot understand this, that all these feelings that they value are all ours, all these thoughts that seem so important to us that they are not needed. We can't understand each other." And he was silent.

The little son of Prince Andrei was seven years old. He could hardly read, he knew nothing. He experienced a lot after that day, acquiring knowledge, observation, experience; but if he had then mastered all these later acquired abilities, he could not have better, deeper understood the full significance of the scene that he saw between his father, Princess Mary and Natasha than he understood it now. He understood everything and, without crying, left the room, silently went up to Natasha, who followed him, looked shyly at her with beautiful, thoughtful eyes; his upturned ruddy upper lip quivered, he leaned his head against it and wept.

From that day on, he avoided Dessalles, avoided the countess who caressed him, and either sat alone or timidly approached Princess Mary and Natasha, whom he seemed to love even more than his aunt, and softly and shyly caressed them.

Princess Mary, leaving Prince Andrei, fully understood everything that Natasha's face told her. She no longer spoke to Natasha about the hope of saving his life. She took turns with her at his sofa and wept no more, but prayed incessantly, turning her soul to that eternal, incomprehensible, whose presence was now so palpable over the dying man.

Prince Andrei not only knew that he would die, but he felt that he was dying, that he was already half dead. He experienced a consciousness of alienation from everything earthly and a joyful and strange lightness of being. He, without haste and without anxiety, expected what lay ahead of him. That formidable, eternal, unknown and distant, the presence of which he had not ceased to feel throughout his life, was now close to him and - by that strange lightness of being that he experienced - almost understandable and felt.

Before, he was afraid of the end. He twice experienced this terrible tormenting feeling of fear of death, the end, and now he no longer understood it.

The first time he experienced this feeling was when a grenade was spinning like a top in front of him and he looked at the stubble, at the bushes, at the sky and knew that death was in front of him. When he woke up after the wound and in his soul, instantly, as if freed from the oppression of life that held him back, this flower of love blossomed, eternal, free, not dependent on this life, he no longer feared death and did not think about it.

The more he, in those hours of suffering solitude and semi-delusion that he spent after his wound, thought about the new beginning of eternal love revealed to him, the more he, without feeling it, renounced earthly life. Everything, to love everyone, to always sacrifice oneself for love, meant not to love anyone, meant not to live this earthly life. And the more he was imbued with this beginning of love, the more he renounced life and the more completely he destroyed that terrible barrier that, without love, stands between life and death. When, this first time, he remembered that he had to die, he said to himself: well, so much the better.

But after that night in Mytishchi, when the woman he desired appeared before him half-delirious, and when he, pressing her hand to his lips, wept quiet, joyful tears, love for one woman crept imperceptibly into his heart and again tied him to life. And joyful and disturbing thoughts began to come to him. Remembering that moment at the dressing station when he saw Kuragin, he now could not return to that feeling: he was tormented by the question of whether he was alive? And he didn't dare to ask.

His illness followed its own physical order, but what Natasha called it happened to him, happened to him two days before Princess Mary's arrival. It was that last moral struggle between life and death in which death triumphed. It was an unexpected realization that he still cherished life, which seemed to him in love for Natasha, and the last, subdued fit of horror before the unknown.

It was in the evening. He was, as usual after dinner, in a slight feverish state, and his thoughts were extremely clear. Sonya was sitting at the table. He dozed off. Suddenly a feeling of happiness swept over him.

“Ah, she came in!” he thought.

Indeed, Natasha, who had just entered with inaudible steps, was sitting in Sonya's place.

Ever since she'd followed him, he'd always had that physical sensation of her closeness. She was sitting on an armchair, sideways to him, blocking the light of the candle from him, and knitting a stocking. (She had learned to knit stockings ever since Prince Andrei had told her that no one knows how to look after the sick as well as old nannies who knit stockings, and that there is something soothing in knitting a stocking.) Her thin fingers quickly fingered from time to time spokes colliding, and the thoughtful profile of her lowered face was clearly visible to him. She made a move - the ball rolled from her knees. She shuddered, looked back at him, and shielding the candle with her hand, with a careful, flexible and precise movement, bent over, picked up the ball and sat down in her former position.

He looked at her without moving, and saw that after her movement she needed to take a deep breath, but she did not dare to do this and carefully caught her breath.

In the Trinity Lavra they talked about the past, and he told her that if he were alive, he would thank God forever for his wound, which brought him back to her; but since then they have never talked about the future.

“Could it or couldn’t it be? he thought now, looking at her and listening to the light steely sound of the spokes. “Is it really only then that fate brought me so strangely together with her in order for me to die? .. Was it possible that the truth of life was revealed to me only so that I would live in a lie?” I love her more than anything in the world. But what should I do if I love her? he said, and he suddenly groaned involuntarily, out of a habit he had acquired during his suffering.

Hearing this sound, Natasha put down her stocking, leaned closer to him, and suddenly, noticing his luminous eyes, went up to him with a light step and bent down.

- You are not asleep?

- No, I have been looking at you for a long time; I felt when you entered. Nobody like you, but gives me that soft silence... that light. I just want to cry with joy.

Natasha moved closer to him. Her face shone with ecstatic joy.

“Natasha, I love you too much. More than anything.

- And I? She turned away for a moment. - Why too much? - she said.

- Why too much? .. Well, what do you think, how do you feel to your heart, to your heart's content, will I be alive? What do you think?

- I'm sure, I'm sure! - Natasha almost screamed, passionately taking him by both hands.

He paused.

- How nice! And taking her hand, he kissed it.

Natasha was happy and excited; and at once she remembered that this was impossible, that he needed calmness.

"But you didn't sleep," she said, suppressing her joy. “Try to sleep…please.”

He released her, shaking her hand, she went to the candle and again sat down in her previous position. Twice she looked back at him, his eyes shining towards her. She gave herself a lesson on the stocking and told herself that until then she would not look back until she finished it.

Indeed, soon after that he closed his eyes and fell asleep. He didn't sleep long and suddenly woke up in a cold sweat.

Falling asleep, he thought about the same thing that he thought about from time to time - about life and death. And more about death. He felt closer to her.

"Love? What is love? he thought. “Love interferes with death. Love is life. Everything, everything that I understand, I understand only because I love. Everything is, everything exists only because I love. Everything is connected by her. Love is God, and to die means for me, a particle of love, to return to the common and eternal source. These thoughts seemed to him comforting. But these were only thoughts. Something was lacking in them, something that was one-sidedly personal, mental - there was no evidence. And there was the same anxiety and uncertainty. He fell asleep.

He saw in a dream that he was lying in the same room in which he actually lay, but that he was not injured, but healthy. Many different persons, insignificant, indifferent, appear before Prince Andrei. He talks to them, argues about something unnecessary. They are going to go somewhere. Prince Andrei vaguely recalls that all this is insignificant and that he has other, most important concerns, but continues to speak, surprising them, with some empty, witty words. Little by little, imperceptibly, all these faces begin to disappear, and everything is replaced by one question about the closed door. He gets up and goes to the door to slide the bolt and lock it. Everything depends on whether or not he has time to lock it up. He walks, in a hurry, his legs do not move, and he knows that he will not have time to lock the door, but all the same, he painfully strains all his strength. And a tormenting fear seizes him. And this fear is the fear of death: it stands behind the door. But at the same time as he helplessly awkwardly crawls to the door, this is something terrible, on the other hand, already, pressing, breaking into it. Something not human - death - is breaking at the door, and we must keep it. He grabs the door, exerting his last efforts - it is no longer possible to lock it - at least to keep it; but his strength is weak, clumsy, and, pressed by the terrible, the door opens and closes again.

The most outstanding exhibit of the ancient collection is the Pergamon Altar, after which the museum is named. The altar is decorated with a grandiose frieze depicting the battle of the gods with the giants.

This is what the Pergamon Altar looks like in the museum hall (photo from Wikipedia)

Around 180-159. BC e. Marble. Altar base 36.44 × 34.20 m

What is this altar, why is it called that and how did it get into the museum in Berlin? That's what I wanted to find out after I saw it with my own eyes. The Internet and Wikipedia helped me with this.

Pergamon- an ancient city off the coast of Asia Minor (now the territory of Turkey), the former center of the influential state of the Attalid dynasty. Founded in the 12th century. BC e. immigrants from mainland Greece.

Here is very interesting article N.N. Nepomnyashchy about how this city was formed, what it was like and what happened to it. http://bibliotekar.ru/100velTayn/87.htm

In memory of the great victory over the barbarian tribe, which was called the "Galatians" (in some sources - the Gauls), the Pergamos erected in the middle of their capital city of Pergamum the altar of Zeus - a huge marble platform for sacrifices to the supreme god of the Greeks.

The relief, which surrounded the platform from three sides, was dedicated to the battle of gods and giants. The giants, as the myth said - the sons of the goddess of the earth Gaia, creatures with a human body, but with snakes instead of legs - once went to war against the gods.

The sculptors of Pergamum depicted on the relief of the altar a desperate battle between gods and giants, in which there is no room for doubt or mercy. This struggle between good and evil, civilization and barbarism, reason and brute force was supposed to remind posterity of the battle of their fathers with the Galatians, on which the fate of their country once depended.

In Pergamon, this building was located on a special terrace on the southern slope of the acropolis mountain, below the sanctuary of Athena. The building consisted of a plinth raised on a five-step foundation, in the western side of which an open staircase 20 m wide was cut. The building of the altar, measuring 36 × 34 m, rested on a four-stage base and reached about 9 m in height. A relief frieze 2.30 m high and 120 m long covered the high smooth wall of the basement and the side walls of the stairs. A jagged cornice completed the upper edge of the frieze.

The legend tells how the giants, the sons of the goddess of the earth Gaia, once decided to attack Olympus and overthrow the power of the gods. According to the prediction of the oracle, the gods could win this fight only if a mortal man came out on their side. Hercules, the son of the god Zeus and the earthly woman Alcmene, is called to participate in the battle.

The large frieze of the Pergamon Altar impresses not only with its grandiose scale and colossal number of characters, but also with a very special compositional technique. The extremely dense filling of the surface of the frieze with high-relief images, leaving almost no free background, is a remarkable feature of the sculptural composition of the Pergamon Altar. The creators of the altar seemed to be trying to give the picture of the combat of the gods and giants a universal character, throughout the frieze there is not a single segment of the sculptural space that is not involved in the active action of a fierce struggle.

The altar, with its famous frieze, was a monument to the independence of Pergamon. But the Pergamonians perceived this victory deeply symbolically, as the victory of the greatest Greek culture over barbarism.

Here is how M.L. Gasparov describes these events in his book "Entertaining Greece":