Fifth and Sixth Crusades. The Sixth Crusade What We Learned

Crusades Nesterov Vadim

Sixth Crusade (1228–1229)

sixth crusade

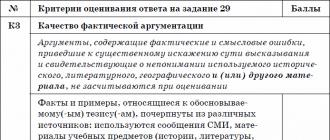

It was held under the leadership of the German emperor and the Sicilian king Frederick II of Hohenstaufen. Frederick was one of the most educated sovereigns of his time: he spoke Greek, Latin, French, Italian, German and Arabic, was interested in natural sciences and medicine. All his life he collected books in different languages and left behind a very large library.

Having accepted the cross back in 1215, Frederick in 1227 went to sea in the direction of the Holy Land, but was forced to return due to an epidemic that had begun in the troops, and then the pope excommunicated him from the church. In 1228, the king nevertheless reached Palestine, where he acted not through military clashes, but through diplomacy, and achieved significant success through negotiations. In exchange for the promise of military assistance to al-Kamil, he, according to the Jaffa Agreement, concluded on February 11, 1229, received Jerusalem.

Louis IX at the head of the crusaders. Source: Guillaume de Saint-Patu, Life of Saint Louis

The agreement took into account mutual interests: the mosques of Omar and al-Aqsa remained with the Muslims, and the Church of the Holy Sepulcher was returned to the Christians. Having fulfilled his vow, having entered Jerusalem, Frederick set sail for his homeland. However, already under the heirs of al-Kamil, the agreement was violated, and in 1244 Jerusalem again fell under the rule of the Muslims.

Attempts to return holy places to Christians were continued by the French king Louis IX the Saint, who organized the Seventh (1248–1254) and Eighth (1270) crusades.

From the book The Complete History of Islam and the Arab Conquests in One Book author Popov AlexanderThe German Crusade and the Campaign of the Nobles In May 1096, a German army of about 10,000 people, led by the small French knight Gauthier the Beggar, Count Emicho of Leiningen and the knight Volkmar, together with the Crusader peasants, staged a massacre

From the book History of the Crusades author Monusova EkaterinaThe "King of Evil" Sixth Crusade 1228-1229 No significant battles took place in this campaign. However, according to its results, the sixth became one of the most successful European military crusades to the East. And it is most interesting for its ornately twisted

From the book The Crusades. Under the shadow of the cross author Domanin Alexander AnatolievichII. The Third Crusade Richard I the Lionheart (From The Chronicle of Ambroise) ... The French king was on his way, and I can say that when he left, he received more curses than blessings ... And Richard, who did not forget God, collected army ... loaded throwing

author Uspensky Fedor Ivanovich7. The Sixth Crusade The peace concluded between Frederick II and the Egyptian sultan ensured peace in the East for more than ten years. Although the Pope for his part recognized the act of the treaty, he did not cease to cherish the hope of initiating a new crusade and

From the book History of the Middle Ages author Nefedov Sergey AlexandrovichTHE CRUSAISE With their swords drawn, the Franks roam the city, They spare no one, even those who beg for mercy... Chronicle of Fulcherius of Chartres. The Pope instructed all monks and priests to preach a crusade for the liberation of the Holy Sepulcher in Jerusalem. Bishops

From the book Short story Jews author Dubnov Semyon Markovich16. Third Crusade In 1187, the Egyptian sultan Saladin (12) took Jerusalem from the Christians and put an end to the existence of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The consequence of this was the third crusade to the Holy Land, which was attended by the German Emperor Frederick

author2. 1st Crusade Clashes between popes and emperors continued for decades, so the crusading movement, organized at the initiative of the pope, initially did not find much response in the German lands. Emperor and his nobles

From the book History of the Military Monastic Orders of Europe author Akunov Wolfgang Viktorovich8. EMPEROR FREDERICK II OF HOGENSTAUFEN (1228-1229) CRUSAISE Along with Frederick I Barbarossa, his great-nephew Frederick II (1212-1250), founder of the University of Naples (1224), was the most famous Roman-German emperor of Hohenstaufen houses

From the book History of the Crusades authorThe campaign of chivalry, or the First Crusade itself Historians traditionally count the beginning of the First Crusade from the departure of the knightly army in the summer of 1096. However, this army also included a considerable number of common people, priests,

From the book History of the Crusades author Kharitonovich Dmitry EduardovichChapter 9 The Sixth Crusade (1227-1229)

From the book Holy Roman Empire: the era of formation author Bulst-Thiele Maria LouiseCHAPTER 43 THE PEACE OF CONSTANCE AND THE SIXTH ITALIAN CAMPAIGN After the fall of Henry the Lion, the emperor was at the height of his power. The authority that the Staufen imperial power at that time enjoyed far beyond the borders of Germany was vividly demonstrated by the court

From the book The Crusades. Volume 2 author Granovsky Alexander Vladimirovich From the book The Age of the Battle of Kulikovo author Bykov Alexander VladimirovichTHE CRUSAD At that time, the Turkish state was gaining strength in the south. Macedonia and Bulgaria were subordinated. In 1394, the Turkish sultan conceived an attack on the very capital of Byzantium. The first step towards this was the blockade of Constantinople. For seven years the Turks blockaded

From the book The Gambino Clan. New generation mafia the author Vinokur BorisCrusade Before Rudolph Giuliani arrived in New York, he worked in Washington for many years, holding high positions in the US Department of Justice. The New York University Law School graduate had a successful career, propelling him through

From the book of God nobles author Akunov Wolfgang ViktorovichCrusade of Emperor Frederick II of Hohenstaufen (1228-1229) Along with Frederick I Barbarossa, Frederick II (1212-1250) was the most famous Roman-German Emperor from the house of Hohenstaufen, whose memory, colored by numerous legends, has survived

From the book Templars and Assassins: Guardians of Heavenly Secrets author Wasserman JamesChapter XXI The Sixth Crusade and the Battle of La Forbie The leader of the Sixth Crusade, which began in 1228, was Frederick II. He was an interesting, extraordinary person: he spoke six languages fluently, including Arabic. Muslims loved and respected him for the following

(1217-1221) ended unsuccessfully for the Christians. Jerusalem remained in the hands of the Muslims, which gave the Pope a reason to call the knights of Western Europe to a new military campaign in the Holy Land. But this time, the church did not need to look for a leader among European monarchs and nobles, since the Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire, Frederick II (1194-1250), was initially considered to be such.

Emperor Frederick II and Egyptian Sultan Al-Kamil agree on the transfer of Jerusalem to Christians

He took an active part in the Fifth Crusade, sending crusaders from Germany to Palestine and Egypt. However, he did not accompany the army, strengthening his position in Germany and Italy. In 1220, Pope Honorius III laid the imperial crown on Frederick's head, and he became the sovereign ruler of the most powerful state in Europe. After that, the emperor swore to the pontiff that he would lead the Sixth Crusade (1228-1229).

The oath was reinforced by marriage to Yolande of Jerusalem, the daughter of the nominal ruler of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, John of Brienne. The wedding took place in 1225, and Frederick II had a vested interest in expanding and strengthening the lands of the Latin East.

Now there was no point in postponing a military company to the Holy Land for an indefinite period, and in 1227 the emperor and his crusaders sailed from Italy to Acre, which at that time was considered the capital of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. However, a plague broke out there, and the German army hastily departed back to Italy.

In the same year, in the month of March, Pope Honorius III died. He was replaced by Gregory IX (1227-1241). This man treated Frederick II extremely negatively. We can say that he was an enemy of the emperor, as he sought to subjugate the lands of Italy, which were under the absolute control of the Catholic Church. Therefore, the new pontiff was looking for any excuse to annoy the ruler of the Holy Roman Empire.

He stated that Frederick II had broken his vow to the cross by leaving Acre. The fact that the plague was rampant there could not serve as an excuse in the opinion of the pope. After such a statement, Gregory IX excommunicated the emperor from the church and thereby freed his subjects from all oaths and obligations to the ruler. Frederick II tried to improve relations with the pope, but he remained adamant, hoping by his decision to weaken the power of the emperor.

Pope Gregory IX excommunicated Frederick II from the Church

I must say that Frederick II was an extremely intelligent and well-educated person. He was fluent in 6 languages, including Arabic. Radel about the well-being of his state and enjoyed great respect among all segments of the German population. Therefore, his authority was not greatly undermined after the excommunication.

Unable to reach an agreement with the pontiff, the emperor again went on the Sixth Crusade in 1228, but at the same time he no longer enjoyed the support of the church. The path of the Germans lay by sea through Cyprus. On this island, the leader of another military expansion to the Holy Land tried to resolve his dynastic claims to the throne of the Kingdom of Cyprus. It was a crusader state created by the English king Richard the Lionheart during the Third Crusade.

Jean I Ibelin sat as regent in it. The German emperor declared that his rule was illegitimate, and the island should fall under the complete control of the Holy Roman Empire. But this initiative did not meet with understanding among the local nobility. As a result, everyone quarreled, and most importantly, Cyprus ceased to consider itself an ally of the German emperor.

After Cyprus, Frederick II went to Acre, where the political situation turned out to be complex and ambiguous. Church ministers reacted extremely negatively to the arrived leader of the Sixth Crusade. But the knights were divided. Some supported the emperor, while others expressed sympathy for the servants of God. Thus, only the crusaders and knights of the Teutonic Order who arrived with him were subordinate to Frederick. With such forces, it was not possible to conduct operations against the Muslims.

What was left to do for the emperor, who fell out of favor with the Pope? He got acquainted with the political situation in the Muslim world and realized that the Sultan of Egypt Al-Kamil was bogged down in suppressing the rebellions in Syria and also did not have sufficient military forces to successfully resist the crusaders. And from this it followed that with a competent approach, it was possible to resolve the issue of returning Jerusalem to Christians without bloody battles.

The German emperor staged a demonstrative demonstration of the huge army he supposedly had. He divided his army into detachments and led them south near the sea coast. For Al-Kamil, this was enough. The Sultan believed in the power of the crusaders and agreed to negotiate. They proved extremely fruitful for the soldiers of Christ. The Muslims gave Jerusalem to the Christians, and in addition gave them such fortresses as Bethlehem, Sidon, Nazareth and Jaffa.

Frederick II with Crusaders and Muslims in Jerusalem

An agreement on this and a truce for 10 years were concluded on February 18, 1229. Already on March 17 of the same year, Frederick II solemnly entered Jerusalem and the next day proclaimed himself king of the Kingdom of Jerusalem. However, the patriarch of the Latin East was absent from the coronation, and therefore this ceremony had no legal force. The newly-made king was not approved by either the pope or the noble feudal lords of the Holy Land. He could only be regent with his son Conrad, born from a marriage with Yolanda of Jerusalem.

In Jerusalem, the German emperor stayed until mid-May 1229 and left for his homeland, where political problems of a local nature arose. This ended the Sixth Crusade. In the same year, the pope canceled the excommunication of Frederick II, guided by the interests of the church. And in the revived kingdom, strife and a struggle for power began. But the most important thing happened: Jerusalem returned to the Christians and was under their complete control in 1229-1239 and in 1241-1244. The same can be said about other areas of the Holy Land.

In conclusion, it should be noted that the crusade led by Frederick II showed the whole world that the most important state issues can be resolved through negotiations, and not on the battlefields. The emperor himself was nicknamed "a crusader without a cross", and his campaign was called "a campaign without a campaign". After all, the soldiers of Christ did not fight the Muslims, but won a complete victory over them, which cannot be said about other military companies in the Holy Land.

The Sixth Crusade was the last successful action of the crusaders in the East. During diplomatic negotiations, Jerusalem was retaken (1229). But 15 years later, the city was recaptured by the Muslims, this time for good.

Preparations for the Sixth Crusade

The main culprit of the failure of the Fifth Crusade, Pope Honorius III declared the German Emperor Frederick II, who never took part in it.

Rice. 1. Emperor Frederick II.

In March 1227 Honorius III died. Gregory IX became the new pope, who severely demanded that Frederick II fulfill his holy vow.

The German emperor obeyed and in August 1227, together with the army, went to sea. On the way, Frederick II fell dangerously ill and made a stop for treatment. Gregory IX considered this a fraud and excommunicated the emperor from the church, which forbade him to take part in the crusade.

Progress of the Sixth Crusade

Frederick II ignored his excommunication. In the summer of 1228 he set out on the Sixth Crusade. In response, Gregory IX excommunicated Frederick II from the church for the second time.

TOP 4 articles

who read along with thisThe enraged Pope called Frederick II a pirate and "servant of Mohammed."

After a short stop in Cyprus, the crusaders arrived in Acre. The local nobility did not support the excommunicated emperor and did not provide military assistance. Since that time, the main events of the Sixth Crusade unfolded in the field of diplomacy.

Rice. 2. A ship off the coast of the Holy Land. Fresco, XII century..

There was also no unity among the Muslims.

The Ayyubid state was divided among themselves by three brothers:

- al-Kamil the Egyptian;

- an-Nasir Daud the Syrian;

- al-Ashraf of Jazeera.

Sultan al-Kamil sent envoys to Frederick II back in 1226 asking for help and offering favorable terms. Arriving in Palestine, the German emperor continued negotiations and at the same time created a bridgehead for an attack on Jerusalem. Khorzmshah Jalal ad-Din was preparing an attack on al-Kamil's possessions, so the sultan hastened to conclude a peace agreement.

The final date of the Sixth Crusade was February 18, 1229. A 10-year peace treaty was signed between the Egyptian sultan and the German emperor.

The main provisions of the agreement:

- Christians get Jerusalem, Bethlehem, Nazareth, the narrow corridor between Jaffa and Jerusalem, and also Sidon;

- In Jerusalem, the Temple Mount with two mosques remains under Muslim rule;

- Christians could rebuild the destroyed walls of Jerusalem;

- all prisoners were released without ransom;

- Frederick II guaranteed the Sultan support against all enemies;

- lucrative trade agreements.

Rice. 3. Emperor Frederick II in the crown of the King of Jerusalem.

Significance and result of the Sixth Crusade

The peaceful capture of Jerusalem was a unique event in medieval diplomacy. Frederick II proved that Muslims can be negotiated. The authority of the German emperor in the Christian world increased significantly.

In 1230, the Pope lifted the excommunication from Frederick II and approved a peace treaty with the Sultan.

After the departure of Frederick II to Europe, a civil war began between the local feudal lords in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The kingdom consisted of scattered cities and castles with no common border. Therefore, soon the Muslims again took possession of the Holy City.

What have we learned?

The leader of the Sixth Crusade was the excommunicated Emperor Frederick II. Despite this, he managed to return Jerusalem to the Christians during the negotiations and win the fight against the Pope.

Topic quiz

Report Evaluation

Average rating: 3.9. Total ratings received: 241.

The peace concluded between Frederick II and the Egyptian sultan ensured peace in the East for more than ten years. Although the pope for his part recognized the act of the treaty, he did not cease to cherish the hope of initiating a new crusade and used all measures in his power to collect donations and stir up the idea of holy places among European Christians. That is why, as soon as the peace period expired, in 1239 a movement began in France and England, headed by King Thibaut of Navarre, Duke Hugh of Burgundy, the Counts of Montfort, Brittany and many others. The emperor assisted the French crusaders, and the pope, fearing that this campaign would only serve to strengthen the imperial party in Jerusalem, now spoke out against the direction of the campaign to the East and indicated another goal: the maintenance of the Latin Empire in Constantinople. Thus, the goal was twofold, depending on the interests of the secular and church parties, and the enterprise was doomed to failure from the very beginning. Some of the crusaders remained true to the original plan and went to Syria, others separated and obeyed the instructions of the pope.

Near Acre, the French detachments united with the Jerusalem troops, but there was no agreement between the two, and most importantly, there was a lack of a plan of action. One detachment marched without the assistance of the Templars and Johnites against the Muslims, but at Gaza they suffered a complete defeat, and the Count of Barsky was killed and the Count of Montfort was taken prisoner. This misfortune was followed by another. Emboldened by their easy success at Gaza, the Muslims decided to take a bold step. Indeed, one of the petty rulers of Syria, Annazir Daoud, attacked Jerusalem, destroyed the fortifications in it and caused terrible devastation in the city. This could lead to the complete destruction of Christian possessions in Palestine, if the Muslim rulers themselves were not in constant war with each other, which gave the Christians the opportunity to stay in the coastal places they occupied. The new reinforcements from England, led by Earl Richard, the nephew of King Richard the Lionheart, did little to help them. But the general situation seemed so deplorable that there was nothing to think about big military enterprises. As a result, Richard rejected the offer of local Christians to enter into an alliance with the Emir of Damascus against the Egyptian Sultan and limited himself to strengthening Acre and Jaffa and renewing the peace treaty with the Sultan in February 1241. Although the French and the British did not do anything important in the East and did not change there was the state of affairs before them, but still the renewed peace treaty with the Sultan secured them from the most serious enemy. It is necessary to ascribe exclusively to the Syrian Christians themselves the responsibility for the coming events that have so damaged them. In the East, as well as in the West, the struggle between secular and spiritual power caused sharp enmity and was accompanied by the formation of parties. The Templars were embittered at the Joannites and the German knights and, with weapons in their hands, attacked their possessions. The side of the first was supported by the Venetians - the strongest representatives of the church party. The supporters of the Roman Curia set out to destroy the imperial party in the East and took advantage of the first opportunity for this. In 1243, Conrad, heir to the crown of Jerusalem, who by that time had reached the age of majority, demanded an oath of allegiance from his eastern subjects. But they contacted the Cypriot queen Alice and offered her to take the kingdom of Jerusalem under her rule. The imperial party, in whose possession the city of Tire was, could not offer strong resistance to the combined troops of the knightly orders and the Venetians and was forced to surrender in Tire. In addition, the opponents of the imperial party, in order to oppose Frederick and his ally, the Egyptian Sultan Eyyub, entered into an alliance with the Sultan of Damascus and the Emir of Kerak (Annazir Daoud), who had recently taken Jerusalem from the Christians. True, this alliance promised Christians important benefits - they again received Jerusalem in their possession and even without the restriction that was in the agreement between Frederick and Alkamil, but such benefits turned out to be illusory, since an alliance with Syrian Muslims could not provide Christians from the powerful Egyptian sultan , who had adherents in Syria and Mesopotamia. The immediate consequence of this ill-considered step was that Sultan Eyyub hired a detachment of Khovarezmians into his service - a tribe that first roamed near the Aral Sea and in the 13th century. who achieved great military glory with his wild raids and unbridled courage. The Khovarezmians put up a detachment of 10 thousand horsemen, who unexpectedly appeared in Palestine, terrifying the population and not giving anyone mercy. When the enemy approached Jerusalem, Patriarch Robert could think of nothing else but to leave the city and escape to Jaffa. When the Christians who remained in Jerusalem fled in fear from the city, a rumor suddenly spread among them that a Christian banner was flying at the gates of the abandoned city. This was an insidious trick of the Khovaresmians, which really deceived many. The fugitives returned to Jerusalem, which they had abandoned, and here they were surrounded by the enemy, who killed up to seven thousand people that day, partly in the city, partly in its vicinity on the road to Jaffa. Having taken possession of Jerusalem, wild predators slaughtered all Christians in it, plundered the churches and did not spare the graves of the Jerusalem kings. This happened in September 1244, and from then on Jerusalem was completely and forever lost to Christians. When the Palestinian Christians recovered from the terrible blow and began to think about the means of salvation, the terrible horde of the Khovarezmians devastated Bethlehem and headed for Gaza, where they joined the troops of the Egyptian sultan. It is true that the Muslim allies of the Christians sent help, but it would be too frivolous to count on the fact that the Muslim troops would zealously fight against their fellow believers. Therefore, the most reasonable solution under the circumstances would be to leave unprotected places to the predators and keep under the protection of the fortress of Ascalon until the enemy ceases to find prey in the devastated country and is forced to retire. But at the council of leaders, the opinion of the Jerusalem Patriarch Robert, who demanded an attack on the army of the Sultan and his allies, prevailed. The battle of Gaza on October 18, 1244, when the Christians were abandoned by their allies and when they had incomparably superior forces against them, turned into a complete defeat and was accompanied either by the beating or capturing of the entire Christian army. After such a brilliant victory, there could be no doubt that the Syrian alliance against Egypt would fall apart. In 1245, Sultan Eyyub took Damascus and thus restored the unity of the Muslim state, which was founded by Saladin and supported by Alkamil and Aladil. In 1247, he took Ascalon from the Christians, so that their possessions in Palestine were now limited to Acre and a few other seaside cities. To complete the disasters at the same time, the Principality of Antioch became the prey of the Mongols. In view of these circumstances, which placed the Christian possessions in the East in an extremely constrained position and threatened to deprive the Europeans of the last fortifications they still held on to, there was no doubt that a new and, moreover, on an extensive scale, an undertaking crusade could not be dispensed with. The news of the events in the Holy Land, which reached Europe in a timely manner, made an extremely depressing impression, and yet the idea of a new crusade did not find sincere adherents for a long time. In fact, Europe, apparently, was already tired of the sacrifices it had suffered, and the Pope of Rome had more interest in European events, where the struggle between secular power and spiritual power attracted all his attention, than in the state of Christian affairs in Palestine. Clever and energetic Innocent IV, encouraging the preaching of the crusade and collecting donations for this purpose, more than once pointed out to those who accepted the cross that the fight against the Hohenstaufen was no less pleasing to God, that the campaign in the Holy Land and calmly turned the money donated for the crusade to the needs of the fight against the imperial troops. There is nothing surprising that, under such circumstances, it was difficult to make a big campaign in Palestine.

In 1248, the crusade of Louis IX took place. It was an undertaking more due to the king's personal character than to public sentiment. Those close to him, on the contrary, tried by all means to cool the ascetic ardor of the king and explain to him the futility of new attempts to achieve such a goal, which is clearly unrealizable, especially in view of the fact that others Christian countries , occupied with internal struggle, are cold about a new campaign in the Holy Land. Louis sent a crusading army to the island of Cyprus, spent the autumn of 1248 and the winter of the following year there, and no doubt, under the influence of the advice of the Cypriot king and representatives of the papal party in Palestine, he made a fatal decision, which was a source of innumerable disasters. Namely, despite the lesson that befell the crusaders in 1219 in Egypt, Louis decided to repeat the attempt of Cardinal Pelagius to "grab the bull by the horns", that is, to attack the sultan in his Egyptian possessions. In the spring of 1249, Louis set out with a huge fleet at sea and landed at the mouth of the Nile, losing a significant part of the ships on the road due to sea storms. The landing followed in the same place where the Crusaders of the Fifth Campaign landed in 1218, that is, near Damietta. Sultan Eyyub lay ill in Mansur, and therefore, at first, Louis was pleased with unexpected successes. So Damietta was occupied almost without resistance, and many stores and weapons were found in it. But in the future, Christians expected a lot of unforeseen difficulties. On the one hand, the events of 1219-1220 were memorable, when the flooding of the Nile caused enormous disasters, on the other hand, a long stay near Damietta had a harmful effect on the discipline of the troops and gave time to the Egyptian sultan to gather fresh forces and disturb the Christians with unexpected attacks on their camp. When they began to discuss the plan of action in Egypt, there was an extreme disagreement in opinion. Some voted in favor of first securing the coastal strip and taking possession of Alexandria, others said that when you want to kill a snake, you must first crush its head, that is, they were of the opinion about a campaign against Cairo. In the campaign of Louis, the same mistake was repeated that was made by Cardinal Pelagius. In November, the French left the camp and went up the Nile. They moved extremely slowly and, as a result, missed the favorable moment that the death of Sultan Eyyub gave them. Approaching the fortress of Mansoure in December, the crusaders had not only significant military forces against them, but also a strong fortification, which could only be taken with the help of siege work. Until Eyyub's heir Turanshah arrived at the scene of hostilities, the crusaders could still count on some success, it was a great happiness for them that, on the instructions of one Bedouin, they found a ford across the canal that separated them from Mansura, and thus approached the walls of the fortress . The siege work progressed, however, slowly, the Egyptians destroyed and burned with the help of Greek fire what the crusaders managed to build, in addition they made sorties and inflicted sensitive defeats on the besiegers. In these battles, the king's brother and many French knights and Templars died. At the end of February 1250, Turanshah arrived at Mansura with new troops from Syria, and the situation of the Christians began to take on a serious character. His first act was to move the fleet to the rear of the crusader camp, as a result of which the Christian army was cut off from Damietta, from where it received food and military supplies. Egyptian partisan detachments intercepted French caravans, Mameluke detachments began to make daring attacks on the camp. This was accompanied by great trouble for the Christians, who began to starve, and the unusual heat was the cause of great mortality. In view of these circumstances, Louis decided to make his way to retreat to Damietta in April 1250. But this retreat took place under extremely unfavorable conditions and was accompanied by the almost complete extermination of the crusading army. During the retreat, King Louis and his brothers Alphonse Poitou and Charles of Anjou were captured, and with them many noble knights. A large number of people were taken prisoner and sold into slavery. Celebrating victory, the Sultan wrote to his governor in Damascus: "If you want to know the number of those killed, then think about the sea sand, and you will not be mistaken." When negotiations began for the ransom of prisoners, King Louis left the queen, who was in Damietta, to decide on her ransom and agreed without any dispute to pay a huge sum of up to ten million francs for the release of the knights from captivity. Under a peace treaty with Turanshah, the French undertook to clear Damietta and not resume war for ten years.

Despite the terrible catastrophe that befell the enterprise of Louis IX, despite all the danger in which Christian possessions found themselves after the victory of the Egyptian sultan, the news that reached Europe did not make such an impression as it had in the 12th century. The Europeans lost faith in the cause of the crusades and did not want to make more fruitless attempts. While most of the knights released from Egyptian captivity returned to their homeland, Louis himself went from Damietta to Acre and here began to consider measures to continue the war. But was it possible to do anything decisive when all his appeals were unsuccessful in France and when they resolutely refused to go to the East? For four more years, Louis remained in Syria, waiting for reinforcements from Europe, reinforcing the fortresses of Acre, Jaffa and Sidon, and giving small battles. At the end of 1252, his mother Blanca, who ruled France in his absence, died, and the general voice of the people demanded that Louis return to his homeland. The king finally yielded to necessity, and in the summer of 1254 set sail from Syria.

The fate of Christian possessions now depended solely on the good will of the Muslim rulers of Syria and Egypt. However, one cannot think that Christians were generally deprived of the means for an energetic struggle. In their hands there were several cities that carried on great trade and served as intermediaries in the exchange of European and Asian goods, in these cities there were a lot of people who owned wealth and luxury. Although the fighting force of the Christians was not great, yet the military establishments and the French detachment left by Louis, with the addition of those crusaders who annually arrived in small numbers from Europe, could inspire some respect among the Muslims. The whole trouble was that Christians had lost the habit of thinking about common interests, and were guided by personal gain, depending on random and momentary whims, they changed their policy: today they were friends with Muslims, and the next day they went over to the camp of their enemies. The Templars and the Johnites jealously watched each other and often entered into open hostility among themselves. The trading people who set the tone for the life of the Syrian cities were distinguished by great moral depravity and unpleasantly struck the newcomer. The biggest disaster for the Syrian Christians was the rivalry between the Italian republics of Venice, Genoa and Pisa and their representatives in the East. The bails of these republics, which had their offices in almost all the cities of Syria, were a powerful aristocracy, which, with its wealth and influence, eclipsed the feudal lords and was in constant enmity with them. It can be argued that trading people and trading interests were the main reason that undermined the existence of Christian dominions. One war of the Genoese with the Venetians, waged in 1256-1258, cost Acre 20 thousand people, in addition, a huge number of ships died in the harbor of Acre and at sea. This war raged almost non-stop in the fifties and sixties of the thirteenth century. and captivated both the Syrian Christians and the Nicene emperors. Apparently, everyone has forgotten that this struggle only hastens the final blow that the Muslims were preparing to deal to the Christian dominions. When the Mongol Khan Gulagu invaded Persia and then conquered Mesopotamia and devastated Syria (1259), a part of the Christians joined the Mongols and thereby aroused extreme irritation among the Muslims, who could not forgive them for an alliance with their bitter enemy.

The Muslim dominions of Egypt and Syria were again united under the rule of Sultan Bibars, who, in his importance and power, resembles Saladin. Setting the main goal of his policy to give the predominance of Islam and finally destroy the European possessions in the East, Bibars did not neglect any means for this and took good advantage of the enmity and opposite currents that he noticed among the Christians themselves. So, he did not lose sight of the important events that were being prepared in the Nicaean Empire, and entered into friendly relations with Michael Palaiologos, who took Constantinople from the Latins. Thus, he valued peaceful relations with Manfred of Sicily and considered it useful to support the imperial party in the East. The apparent reluctance of European Christians to make new sacrifices for campaigns in the East and the indifference of Syrian and Palestinian Christians to common interests gave Sultan Bibars ample opportunity to appreciate the comparative advantages of the Muslims and seize the favorable moment to put an end to Christian dominions. In 1262, he undertook the first campaign in Syria, and then within six years he repeated these campaigns four times. The consequence of his successful wars was that he took Antioch from the Christians, took Caesarea, Arsuf and Jaffa, devastated the environs of Tire and Acre. It cannot be said that Bibars got these successes very dearly, he never had the united forces of Christians against him, but defeated separate detachments of the Jerusalem and Antioch barons, hospitalites, Johnites and Cypriot knights. It is difficult to find a more expressive characterization of the moral and political position of Eastern Christians than the following words of Bibars, spoken in response to the petition of Charles of Anjou for his co-religionists: the greatest".

The brilliant successes of Bybars and the desperate pleas for help from Syria once again created a significant movement in favor of the crusade. King Louis IX of France became the head of this movement for the second time. One can marvel at the perseverance of Louis, with which he pursued his cherished goal, despite the hard lesson learned from the First Campaign. Perhaps he could have prolonged the dominance of Christians in Syria for several years, if he had backed them up with fresh forces, but now it was too late to dream of inflicting a sensitive blow on the Muslims. When, in 1270, the French knights, with the king, his brothers and sons at the head, boarded the Genoese ships, the direct goal of the campaign, apparently, had not yet been determined. She first became famous in Cagliari (in Sardinia), where a military council was held and where it was decided to go to Tunisia. Outwardly, this campaign was motivated by the fact that the Tunisian emir allegedly showed a penchant for Christianity and that by bringing him into the bosom of the Catholic Church, one could acquire an important ally for the subsequent war with the Egyptian sultan. But in fact, Louis in this respect was the instrument of a clever intrigue, which was probably prepared in Sicily and which aimed at subordinating Tunisia to the political power of the Sicilian kingdom, which had recently passed to the French royal house. In any case, the Tunisian campaign was an undertaking that very little corresponded to the goals and needs of Christians in the East. It turned out to be such in its consequences. Having landed on the Tunisian coast on July 17, 1270, Louis not only did not meet the willingness of the Tunisian Muslims to accept Christianity, but, on the contrary, had an enemy in them who was ready to defend himself. Without starting, however, serious enterprises against Tunisia and waiting for the arrival of Charles of Anjou, the French gave the emir time to gather strength and establish relations with Sultan Bibars. The only acquisition of the crusaders was the conquest of the Carthaginian fortress, which, however, did not matter to them. Meanwhile, the Emir of Tunis began to disturb the Christian camp with attacks, and the unaccustomed African heat produced illness and great mortality. In early August, the king's son Tristan died, then death overtook the papal legate, Bishop Rudolf, and finally fell into a serious illness, from which he went to the grave on August 25, and the king himself. The whole crusading enterprise was upset by this. After several battles with the Tunisian troops, finding neither the desire nor the important motives to spend forces on the siege of the strongly defended city, Louis's heir Philip and Charles of Anjou began negotiations for peace. Both parties agreed to the following terms:

1) the Tunisian emir gives freedom to Christians to live in his areas and to worship in the temples they have built;

2) agrees to pay double, against the former, tribute to the Sicilian king, pays military expenses.

For their part, the Christian kings undertook to immediately clear the areas of Tunisia they had occupied. Most of the knights considered their vow fulfilled and returned to their homeland. Only a small part of the French and Prince Edward of England considered it an obligation to go to Syria.

In 1221, the rest-bearers of the Fifth campaign concluded a peace with the Egyptian Sultan al-Kamil (name: Nasir ad-Din Muhammad ibn Ahmad, title: Sultan al-Malik al-Kamil I), according to which they received a free retreat, but pledged to clear Damietta and Egypt in general.

Meanwhile, Frederick II of Hohenstaufen married Jolanthe, daughter of Mary of Jerusalem and John of Brienne. He pledged to the pope to launch a crusade.

Frederick in August 1227 indeed sent a fleet to Syria with Duke Henry of Limburg at the head; in September, he sailed himself, but had to return to the shore soon, due to a serious illness. Landgrave Ludwig of Thuringia, who took part in this crusade, died almost immediately after landing in Otranto.

Pope Gregory IX did not respect Frederick's explanations and pronounced excommunication over him because he did not fulfill his vow at the appointed time.

An extremely harmful struggle between the emperor and the pope began. In June 1228, Frederick finally sailed to Syria, but this did not reconcile the pope with him: Gregory said that Frederick (still excommunicated) was going to the Holy Land not as a crusader, but as a pirate.

In the Holy Land, Frederick restored the fortifications and in February 1229 concluded an agreement with Al-Kamil: the Sultan ceded to him, and some other places, for which the emperor undertook to help Al-Kamil against his enemies.

Chris 73, Public DomainIn March 1229, Frederick entered Jerusalem, and in May he sailed from the Holy Land. After the removal of Frederick, his enemies began to seek to weaken the power of the Hohenstaufen both in Cyprus, which had been a fief of the empire since the time of Emperor Henry VI, and in Syria. These strife had a very unfavorable effect on the course of the struggle between Christians and Muslims. Relief for the crusaders was brought only by the strife of the heirs of Al-Kamil, who died in 1238.

In the autumn of 1239, Thibaut of Navarre, Duke Hugh of Burgundy, Duke Pierre of Brittany, Amalrich of Montfort and others arrived.

And now the crusaders acted discordantly and recklessly and were defeated; Amalrich was taken prisoner. Jerusalem again fell for some time into the hands of one ruler.

The alliance of the crusaders with Emir Ishmael of Damascus led to their war with the Egyptians, who defeated them at. After that, many crusaders left the Holy Land.

Arriving in the Holy Land in 1240, Count Richard of Cornwall (brother of the English king Henry III) managed to conclude a favorable peace with the Ayyubid sultan al-Malikas-Salih II), the ruler of Egypt.

Meanwhile, strife among the Christians continued; barons hostile to the Hohenstaufen transferred power over Alice of Cyprus, while the son of Frederick II, Conrad, was the legitimate king. After the death of Alice, power passed to her son, Henry of Cyprus.

The new alliance of Christians with the Muslim enemies of the Ayyubids led to the fact that they called for help the Turks-Khorezmians, who in September 1244 took Jerusalem, returned to the Christians shortly before, and terribly devastated it. Since then, the holy city has been forever lost to the crusaders.

After a new defeat of the Christians and their allies, the Ayyubids took Damascus and Ascalon. The Antiochians and the Armenians were at the same time obliged to pay tribute to the Mongols.

In the West, the crusading zeal cooled down, due to the unsuccessful outcome of the last campaigns and due to the behavior of the popes, who spent the money collected for the crusades on the fight against the Hohenstaufen, and declared that with the help of the Holy See against the emperor, one could be freed from the earlier vow to go to the Holy Land.

However, the preaching of the crusade continued as before and led to the 7th crusade.